The Christmas Truce Revisited | @RichEvansWriter

Less 'Moneyball' and more ‘Military-ball’ – how might the sides have lined up on that famous Christmas Day in 1914? @RichEvansWriter takes another look at the Christmas Truce, that story has it, saw a football match take place during a ceasefire in the trenches.

The honour roll of professional footballers who perished in the First World War makes for a long, sobering reading. Names have been meticulously cross-referenced against regimental diaries and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, but it is worth remembering that, for inclusion, players had to have played professionally prior to the end of the 1914/15 season. Set against the unspeakable horrors of mechanised slaughter, the fact that the casualties were footballers at all becomes somewhat incidental. After all, just over three hundred dead in the context of almost a million in total from British shores seems rather miniscule.

Footballing questions abound. For example, what might some of the lost have gone on to achieve had they been born in another era? What might the casualty list have looked like had the Football Battalion never existed? A Pals Battalion, formed in 1915, it concentrated footballing talent into theatres like Arras and the Somme; a notable recruit included Second Lieutenant Walter Tull. Another pressing question is, what really happened in the infamous Christmas Truce match of 1914. The fabled event has passed into folklore and the years have misted its memories, but might some contemporary professionals have featured? Might there have been a similar smattering of footballing talent on the German side? How good might the standard of a match in No-Man’s-Land have been?

Yes, its all idle speculation and no - it’s not like the line-ups could ever be confirmed, but it is worth remembering that only seven of the professional footballers from Britain who lost their lives had perished by the War’s first Christmas. Among them were William Sutherland (the first footballing casualty of the conflict) who played for Plymouth Argyle and Southend United; Larrett Roebuck of Huddersfield Town; James Hastie and William Brewer whose names both appear on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, and the final casualty of the first year of the War: Frederick Costello of Southampton and West Ham United renown. Macabre considerations notwithstanding, that would have left quite a pool of players available to turn out with khaki tunics for goalposts.

Of course, many of those professional players who later fell would not have been on the front lines at the time, much less in the vicinity of Neuve-Chapelle where the truce was centred. Short truces occurred fairly frequently to allow for the collection of the slain, but did so unpredictably and without advance warning. Approaching December 1914, British suffragettes signed an open letter to the women of Germany and Austria demanding one. Pope Benedict XV echoed their sentiments, pleading that ‘the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.’ His overture was refused by both sides but, while High Command urged business-as-usual, those in the trenches were in defiant mood. One can only assume that, beyond the barbed wire, and growing tired of trading tobacco, coffee and photographs with their grey-uniformed counterparts, thoughts turned to the beautiful game.

Reports vary, but The Times newspaper on 1st January 1915 reported a ‘football match played between them and us’. Robert Graves, revisiting the supposed fixture while writing a later story, had the scoreline at 3-2 in favour of Germany. Elsewhere, the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders reportedly defeated a German side 4-1 and, in Ypres, the Royal Field Artillery claimed to have played a Prussian side with a bully beef ration tin serving as a makeshift ball. The sheer number of alleged games muddies the already muddied ground still further. All that can be certain is that the quality of pitches would doubtless have rivalled the Maracanã circa 1986 in the stakes of unevenness.

So, would the games have been any good? Probably not. Does it matter? Almost certainly not.

The Football Battalion didn’t reach the front line for another year and it was not until 1916 that representatives of Heart of Midlothian were photographed in France – 16 of its players enlisted, making them the first team to volunteer en masse. In reality, there may well have been very few professional footballers available for selection in No Man’s Land on Christmas Day 1914. After all, the domestic season was still underway with Everton set to win the League and Derby County to top the Second Division. In terms of how much of a contest the fabled matches would have been, things are even more uncertain; there is far less information available about German footballers who perished in the First World War. Football in Germany, it must be remembered, was played at an amateur level until 1949, when semi-professional leagues were introduced and it wasn’t until the 1963/64 season that the Bundesliga was born.

And yet this brief moment still has a hold on the collective imagination. While playing the eponymous role in Blackadder Goes Forth, Rowan Atkinson’s character references it, spitting vitriol about a refereeing decision in the match: ‘I was never offside! I could not believe that decision'. Over the years, Christmas Truce football has grown into a metaphor - a glimmer of hope in a sea of despair. But if football won the day, there is no doubt who lost it; that young men could switch from festivity to hostility so quickly seems almost unthinkable. In Wilfred Owen’s Strange Meeting, the poet details an eerie encounter with a foreign soldier: ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’ - a line that perhaps sums up the futility of the shattered truce better than any other. It was certainly a one off - the powers that be were eager for it not to be repeated and issued express orders to prohibit such fraternization in subsequent years.

Another poet, Philip Larkin wrote in MCMXIV, ‘Never such innocence again’ when viewing sepia pictures of enthusiastic crowds enlisting through the lens of hindsight. Maybe a little of this innocence still persisted in the War’s first Christmas; it had certainly evaporated by the end of 1915. Perhaps this is why the Truce still captures the imagination. If we are to cite any sense of sport’s positive influence, then it’s surely better to use this than the East Surrey Regiment’s hubristic punting of footballs before them as they advanced on the morning of 1st July 1916.

The last word is best reserved for Major Frank Buckley, commander of the Football Battalion. Its formation was largely a result of pressure exerted by Punch Magazine and, writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle; they urged footballers to play more active military roles. Buckley played for both Manchester clubs, Aston Villa, Brighton & Hove Albion,

Birmingham, Derby County and Bradford City before the War, and then Norwich City after it. In the mid-1930s, he wrote that over 500 of the battalion’s 600 original men (among them Edwin Latheron – probably the War’s most famous casualty in purely footballing terms) were deceased – either killed in action or having died subsequently as a result of their wounds.

When faced with numbers like that, one is left to wonder whether the quality of one match really mattered at all.

©The Football History Boys, 2021

The honour roll of professional footballers who perished in the First World War makes for a long, sobering reading. Names have been meticulously cross-referenced against regimental diaries and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, but it is worth remembering that, for inclusion, players had to have played professionally prior to the end of the 1914/15 season. Set against the unspeakable horrors of mechanised slaughter, the fact that the casualties were footballers at all becomes somewhat incidental. After all, just over three hundred dead in the context of almost a million in total from British shores seems rather miniscule.

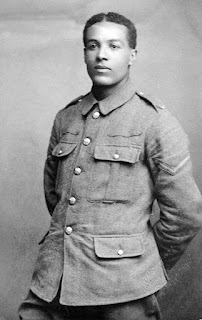

Footballing questions abound. For example, what might some of the lost have gone on to achieve had they been born in another era? What might the casualty list have looked like had the Football Battalion never existed? A Pals Battalion, formed in 1915, it concentrated footballing talent into theatres like Arras and the Somme; a notable recruit included Second Lieutenant Walter Tull. Another pressing question is, what really happened in the infamous Christmas Truce match of 1914. The fabled event has passed into folklore and the years have misted its memories, but might some contemporary professionals have featured? Might there have been a similar smattering of footballing talent on the German side? How good might the standard of a match in No-Man’s-Land have been?

|

| Walter Tull |

Yes, its all idle speculation and no - it’s not like the line-ups could ever be confirmed, but it is worth remembering that only seven of the professional footballers from Britain who lost their lives had perished by the War’s first Christmas. Among them were William Sutherland (the first footballing casualty of the conflict) who played for Plymouth Argyle and Southend United; Larrett Roebuck of Huddersfield Town; James Hastie and William Brewer whose names both appear on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres, and the final casualty of the first year of the War: Frederick Costello of Southampton and West Ham United renown. Macabre considerations notwithstanding, that would have left quite a pool of players available to turn out with khaki tunics for goalposts.

Of course, many of those professional players who later fell would not have been on the front lines at the time, much less in the vicinity of Neuve-Chapelle where the truce was centred. Short truces occurred fairly frequently to allow for the collection of the slain, but did so unpredictably and without advance warning. Approaching December 1914, British suffragettes signed an open letter to the women of Germany and Austria demanding one. Pope Benedict XV echoed their sentiments, pleading that ‘the guns may fall silent at least upon the night the angels sang.’ His overture was refused by both sides but, while High Command urged business-as-usual, those in the trenches were in defiant mood. One can only assume that, beyond the barbed wire, and growing tired of trading tobacco, coffee and photographs with their grey-uniformed counterparts, thoughts turned to the beautiful game.

Reports vary, but The Times newspaper on 1st January 1915 reported a ‘football match played between them and us’. Robert Graves, revisiting the supposed fixture while writing a later story, had the scoreline at 3-2 in favour of Germany. Elsewhere, the Argyle and Sutherland Highlanders reportedly defeated a German side 4-1 and, in Ypres, the Royal Field Artillery claimed to have played a Prussian side with a bully beef ration tin serving as a makeshift ball. The sheer number of alleged games muddies the already muddied ground still further. All that can be certain is that the quality of pitches would doubtless have rivalled the Maracanã circa 1986 in the stakes of unevenness.

|

| Various newspapers reported stories of a 'Christmas Truce'. |

So, would the games have been any good? Probably not. Does it matter? Almost certainly not.

The Football Battalion didn’t reach the front line for another year and it was not until 1916 that representatives of Heart of Midlothian were photographed in France – 16 of its players enlisted, making them the first team to volunteer en masse. In reality, there may well have been very few professional footballers available for selection in No Man’s Land on Christmas Day 1914. After all, the domestic season was still underway with Everton set to win the League and Derby County to top the Second Division. In terms of how much of a contest the fabled matches would have been, things are even more uncertain; there is far less information available about German footballers who perished in the First World War. Football in Germany, it must be remembered, was played at an amateur level until 1949, when semi-professional leagues were introduced and it wasn’t until the 1963/64 season that the Bundesliga was born.

And yet this brief moment still has a hold on the collective imagination. While playing the eponymous role in Blackadder Goes Forth, Rowan Atkinson’s character references it, spitting vitriol about a refereeing decision in the match: ‘I was never offside! I could not believe that decision'. Over the years, Christmas Truce football has grown into a metaphor - a glimmer of hope in a sea of despair. But if football won the day, there is no doubt who lost it; that young men could switch from festivity to hostility so quickly seems almost unthinkable. In Wilfred Owen’s Strange Meeting, the poet details an eerie encounter with a foreign soldier: ‘I am the enemy you killed, my friend’ - a line that perhaps sums up the futility of the shattered truce better than any other. It was certainly a one off - the powers that be were eager for it not to be repeated and issued express orders to prohibit such fraternization in subsequent years.

|

| The Truce is even referenced in iconic TV show Blackadder. |

Another poet, Philip Larkin wrote in MCMXIV, ‘Never such innocence again’ when viewing sepia pictures of enthusiastic crowds enlisting through the lens of hindsight. Maybe a little of this innocence still persisted in the War’s first Christmas; it had certainly evaporated by the end of 1915. Perhaps this is why the Truce still captures the imagination. If we are to cite any sense of sport’s positive influence, then it’s surely better to use this than the East Surrey Regiment’s hubristic punting of footballs before them as they advanced on the morning of 1st July 1916.

The last word is best reserved for Major Frank Buckley, commander of the Football Battalion. Its formation was largely a result of pressure exerted by Punch Magazine and, writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle; they urged footballers to play more active military roles. Buckley played for both Manchester clubs, Aston Villa, Brighton & Hove Albion,

Birmingham, Derby County and Bradford City before the War, and then Norwich City after it. In the mid-1930s, he wrote that over 500 of the battalion’s 600 original men (among them Edwin Latheron – probably the War’s most famous casualty in purely footballing terms) were deceased – either killed in action or having died subsequently as a result of their wounds.

When faced with numbers like that, one is left to wonder whether the quality of one match really mattered at all.

|

| The Truce is now remembered in statue form with a football present |

By Rich Evans, written for @TFHB

(All pictures borrowed and not owned in any form by TFHB)

Comments