1940: When Asbjørn Halvorsen’s Bronze Team Didn’t Play | Brendan Husebo

In 1940, Norway's Asbjørn Halvorsen could’ve just been a football man, but he inspired the resistance. Let's find out some more about:

The General

The Boss

The Bronze Team

The Captain

The Keeper

The Westerner

The Whisperer

The Spirit

|

| Asbjørn Halvorsen |

Asbjørn Halvorsen wasn’t a relatable man. He was a polymath. He was his generation’s best footballer, and then their best coach. He spoke multiple languages and was an adept politician. His friendship would save the life of and inspire a future prime minister. His control of language would save the lives of hundreds of others. His executive control of football would pave the way for the modern

league system in Norway.

But he didn’t have to be any of those things. He could have just been a football man. It’s worth relating to that fact alone when remembering July 1940, three months into occupation, when ‘Assi’, as he was known, was summoned into Oslo’s parliament building. He was to face Josef Terboven, the Reichskommissar for Norway, the most powerful Nazi in the country, a man Joseph Goebbels would describe as too violent.

Terboven was flanked by every upper military personnel in the country. Halvorsen was outnumbered, surely aware of the meeting’s gravity. They wanted a football match. Germany and the Norwegian national team were to play in September. It would be a way to commemorate, celebrate and welcome Norway’s new Nazi administration. The Reichskommissar had been directed towards the football association’s generation secretary to organise the game. Terboven’s men assured Halvorsen that they’d provide the appropriate policing and security. All Assi had to do was get his team on the pitch.

|

| Norway's Reichskommissar, the evil Josef Terboven |

The conversation took place entirely in German. Halvorsen, born half-an-hour from the Norway-Sweden border, left Sarpsborg for Germany in 1921 as a 23-year old. In 12 years at Hamburg SV, he became the captain and linchpin. He built the city a respected insurance company. He was a celebrity in Germany, more so than was ever possible in Norway.

The Third Reich remembered Halvorsen, the centre half general, from before their rise, creating countless goals to fill that Hanseatic trophy cabinet. “He’ll go down in history, this hard but never unfair man,” wrote die Fußball-Woche upon his HSV departure. The Reich wanted him back, this time as the general of his country’s athletes. And, the role of Nazi-sports was simple: to assimilate Halvorsen’s people by way of propaganda, to make them feel like their country wasn’t just some naval trade route but an important part of the future of this world.

Nowadays, we’d call it what? Sportswashing.

|

| Whilst 'sportswashing' is a modern term, the Nazis were not unfamilar to it |

As football fans, we’ve all experienced football’s biggest appeal, and we’ve felt the appeal’s contradiction: 22 players on a pitch, 11-a-side, with a referee between - the great leveller. We’re given an equal playing field and, against all the odds, a team of country bumpkin nobodies can beat die wunderkinder. Except, because we’re human with real and complex experiences, we know that meritocracy is never as it’s promised. Yet still, we suspend belief because it is fundamentally satisfying to see the very best players prove that’s what they are.

In 2023, eight decades since Halvorsen went to the Storting, we’re suspending that belief perhaps more than any time since. But, deep down, we surely know it’s not real. We know that football isn’t actually meritocratic. We know that the world isn’t fair. We know our sport shouldn’t be used to prove something that is not. The spirit of football is complex, the essence of why we play and watch is totally abstract, and to bastardise it is to reject our civility.

So, what would you be willing to allow happen in exchange for fame and glory in football? What would you allow as a fan to watch your favourite club or country’s greatest generation reach ultimate sporting glory? What would you think if, in the middle of that generation’s peak, they simply refused to continue playing?

Assi didn’t organise the Nazis their game. In the July meeting, Halvorsen told Terboven and his bully boys not to bother finding security and police. He told them that, even if he did, the stadium would be empty. To the apparent astonishment of the men in the room, he explained to them that even every child in Norway was aware that they weren’t a part of the Reich. They were at war with it.

Halvorsen could have just been a football man, but he was a man who walked into that room unafraid of his occupiers.

Four months later, in November 1940, three-hundred thousand athletes, ten percent of the country, collectively agreed with Halvorsen. They acted upon the belief that the spirit of their sports was not to be used as a tool for the Nazi regime. They led what still is the largest strike in sports history. Idrettsboikotten (‘the Sports Boycott’) had begun. For almost 2,000 days, till the day of their liberation, the people of Norway rejected public sport. Sportswashing would not work. Idrettsfronten (‘the Sports Front’) became the first Norwegian civil resistance movement of World War II, and would later act as the guideline for the entire Norwegian resistance movement.

.jpg) |

| An empty Bislett stadium in 1942, during the Idrettsboikotten |

40 days prior, a record crowd of 32,000 marked the Norwegian Cup final, which proved to be the last non-underground football match for 5 years. Halvorsen had, at first, threatened to lead a boycott for the game if Nazi insignia were made mandatory. Assi then personally denied Terboven access to the royal stand. The national anthem had been banned and the royal family had fled. Yet, still, ‘Ja vi elsker’ rang out at kick-off and the royal box, empty for the first and only time, became a symbol of resistance. A football crowd is a spiritual gathering, a football game is a metaphysical escape, and they tried to deny the liberty that brings.

The Boss

Halvorsen left Germany in 1933 for exactly the reasons imaginable. The constituency of Hamburg was a last bastion for the German Social Democratic Party, but the NSDAP had just gained a majority. Pictured in his testimonial for HSV, Halvorsen’s hands hung by his sides as his newly former teammates stood performing what was then still called the ‘German salute’. Sport had become nazified, even Hamburg had turned, and the Reichskommissariat in Oslo really should have known what sort of human their hero Assi wanted to be by 1940.

Halvorsen left Germany in 1933 for exactly the reasons imaginable. The constituency of Hamburg was a last bastion for the German Social Democratic Party, but the NSDAP had just gained a majority. Pictured in his testimonial for HSV, Halvorsen’s hands hung by his sides as his newly former teammates stood performing what was then still called the ‘German salute’. Sport had become nazified, even Hamburg had turned, and the Reichskommissariat in Oslo really should have known what sort of human their hero Assi wanted to be by 1940.

For the two years following the meeting with Tervoben, Halvorsen was consistently asked to mediate meetings between the Norwegian sports federations and the Reich. He was told he could become the Sportführer of Norway, to join a department he and his team had personally embarrassed in Berlin at the 1936 Olympics. He knew their language, the people, the so-called ‘German spirit’. But he was Norwegian, he was on strike and he was at war.

Halvorsen had quickly risen to general secretary within the Norwegian football association. When Halvorsen first returned, he acted as pitch inspector for less than a year before it was evident his ability as a player translated into that of an executive. Part of his assignment was to become head coach of the national team, which had sunk to a low they hadn’t expected by 1935. The pitch inspector was being asked to become the saviour.

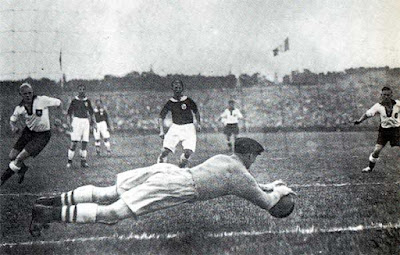

In the 1920 Olympics, Norway handed Great Britain their first-ever tournament defeat. To this day, it’s the biggest upset ever by Elo-ratings, and a match that would propel a 22-year old Halvorsen towards Germany. But, till his fateful return, it was football wilderness for Norway. Assi would introduce the WM formation, he’d instil a greatly increased physical and tactical regimen, and he’d quickly discern the balance between the individually liberal ‘Norwegian spirit’ the players knew with the systematic ‘German spirit’ he had learnt. Qualification to the 1936 Berlin Olympics quickly went from impossibility to packing bags in preparation.

|

| Norway's side that beat Great Britain 3-1 in the 1920 Olympics |

The Bronze Team

Much has been spoken of 7th August 1936, the day Adolf Hitler watched his first and only football match. Convinced to forgo a trip to the rowing, he was promised a thrashing of little village Norway. Egil Olsen led Norway to rank #2 in the world with those famous wins over Brazil in the ’90s. Erling Haaland, Martin Ødegaard and Antonio Nusa will be watched, remembered and loved by billions of people. But no ‘golden generation’ will surmount the Bronze Team that defeated Nazi Germany at their own Olympics in front of Adolf Hitler.

Much has been spoken of 7th August 1936, the day Adolf Hitler watched his first and only football match. Convinced to forgo a trip to the rowing, he was promised a thrashing of little village Norway. Egil Olsen led Norway to rank #2 in the world with those famous wins over Brazil in the ’90s. Erling Haaland, Martin Ødegaard and Antonio Nusa will be watched, remembered and loved by billions of people. But no ‘golden generation’ will surmount the Bronze Team that defeated Nazi Germany at their own Olympics in front of Adolf Hitler.

Magnar Isaksen, a man who most in Norway were shocked to even be picked in the squad and a man Hitler mistakenly perceived to be Jewish, scored 7 minutes after kick-off and 7 minutes before full-time. A rhyming and orderly Nazi disaster: most poetic. All the pre-planning, training and possession in the world isn’t enough in football. This is a sport where country bumpkin nobodies can travel down to Berlin and defeat the finest, purest athletes. This is the beauty of it all. This is its spirit, the great leveller, and exactly the reason it was forever sullied in Adolf Hitler’s eyes from when he stormed off in that 83rd minute.

Halvorsen’s team could have just been football men. In 1936, they only lost in the 96th minute to eventual gold medalists, Fascist Italy. Arne Brustad, known as the ‘the Italian of the North’ for his ‘Mediterranean temperament’, scored a hat trick in front of 95,000 people in the bronze medal match against Poland. At the 1938 World Cup, was it déjà vu? They’d go on to lose to an offside goal against the eventual winners, Fascist Italy.

The team’s legacy was shining, if buffed out a bit by being the ‘nearly men’. If they had played that game in September 1940, they would have still won the bronze in 1936, and they’d have still come closest to taking down the winners in 1938. They would have, to this day, been the most successful men’s Norwegian team. But, they would have just been football men.

|

| The Bronze Team at the 1936 Berlin Olympics |

The Captain

Jørgen Juve, till Erling Haaland takes over, is still Norway’s all-time top scorer despite playing as a right back and centre half for a large part of his international career. The captain was theHalvorsen of the Bronze Team, the man of the match that day in Berlin. His feet were a magnet for the ball, and the Germans would quickly see the ball in their own half again if it went anywhere near Juve. By 1940, he had stopped playing and was transitioning acceptingly to a coaching career. He could have just been a football man.

Jørgen Juve, till Erling Haaland takes over, is still Norway’s all-time top scorer despite playing as a right back and centre half for a large part of his international career. The captain was theHalvorsen of the Bronze Team, the man of the match that day in Berlin. His feet were a magnet for the ball, and the Germans would quickly see the ball in their own half again if it went anywhere near Juve. By 1940, he had stopped playing and was transitioning acceptingly to a coaching career. He could have just been a football man.

But, far from it, he was perhaps the country’s leading sports journalist. During the 1936 Olympics, he most notably wrote, “Germany has thrown overboard her old precious culture … [Nazi-ruled Berlin] completely lacks the tradition necessary to give the Olympic Games a true spiritual frame.”

Juve was in Prague as foreign correspondent in 1939 when Germany broke the Munich Pact to invade Czechoslovakia. In 1940, he followed Norwegian volunteers to the Northern Finnish front in the Winter War. When Norway was invaded, he joined the Norwegian Army at once. He turned down countless bribes to become editor of Nazi-controlled newspapers. In 1941, he edited the Norwegian embassy in Stockholm’s magazine alongside Rolf Gerhardsen, brother of the longest-serving prime minister Einar. He helped administer the Norwegian merchant navy, which most notably carried aviation fuel for the Hawker Hurricanes and Spitfires prior to the Battle of Britain. He hosted ‘The Spirit of the Vikings’, a radio show for WNYC, which would give North America the most human insight into Norway’s suffering during the War. He interviewed King Haakon,

Kon-Tiki explorer Thor Heyerdahl, Nobel Prize-winning author Sigrid Undset amongst others to speak of being Norwegian during the War. He married famed psychologist and the first Miss Norway, Eva Røine. Speaking on his radio show about the sports strike, he told his US listeners, “Imagine a swarm of locusts invading your home, settling on everything that is yours, desecrating every symbol of your everyday life. You can’t just leave that be and play a game of football. Until the scum is cleared away, there can be absolutely no diversion.”

Jørgen Juve was not just a football man.

|

| Jørgen Juve in 1931 |

The Keeper

It was written that, “as a tennis player, he enjoyed admiration around Oslo. As a bandy and ice hockey player, he was feared across large parts of the country. As a ski jumper, he was known nationally.” Yet it was on the football pitch where Henry ‘Tippen’ Johansen was said to have single-handedly won several of the 48 games he played in goal for Norway.

During his 23 football playing years, four of which were underground after 1940, Tippen played exclusively for Vålerenga, Oslo’s working-class club. He’d compete for the ‘The Pride of Oslo’ in his four other sports. He’d coach the football team through two separate periods. He could have just been a football man. He could have just been a ski man, tennis man, ice hockey man, bandy man.

But, on 8th May 1945, Tippen was amongst the resistance fighters sent to Skaugum, in normal years the home of the Crown Prince but instead then the residence of Josef Terboven during occupation. He was sent to arrest the man who wanted to sportswash away his iron fist and murderous rule. Terboven detonated 50 kilograms of dynamite in Skaugum’s bunker before Tippen and his men could get to him. Josef Terboven died a coward. But Henry ‘Tippen’ Johansen was not just a football man.

|

| Henry ‘Tippen’ Johansen in the 1930s |

The Westerner

Reidar Kvammen was the only man in the Bronze Team to come from Stavanger. Two were from Bergen, eight from Oslo and two from the south-east/Oslo area. Despite being the geographical outsider, Kvammen was the purest, most talented footballer Norway had ever seen. Arne Brustad from the left would put the ball in the net, but it was the inside right that repeatedly stunned defences from around Europe.

Reidar Kvammen was the only man in the Bronze Team to come from Stavanger. Two were from Bergen, eight from Oslo and two from the south-east/Oslo area. Despite being the geographical outsider, Kvammen was the purest, most talented footballer Norway had ever seen. Arne Brustad from the left would put the ball in the net, but it was the inside right that repeatedly stunned defences from around Europe.

Barely 23, his talent shone brightest when Norway defeated Ireland to qualify for the 1938 World Cup. In the consequential loss to Fascist Italy, he’d shine again as Norway’s best. Both times, George Allison invited him to play for Arsenal. Both times, which he later said he regretted, Kvammen declined. If not for fear of culture shock, he’d have been champion of England, perhaps a legend in North London. But, had he done so, he would have undoubtedly been just a football man.

Instead, he was a policeman in a city of 50,000 people about to be occupied. By 1940, the most talented footballer Norway had seen was arrested for refusing to work for his occupiers. Norway’s best footballer was being sent to Grini Concentration Camp in Oslo, and then to Stutthof, 20 miles east of Gdańsk. He returned home five years later a hero of honour. But he returned home injured. He returned home a prisoner who had watched the War from Poland.

Perhaps it was spite that inspired him, but he played himself back into the national team through every injury. He became the first Scandinavian to play for his nation 50 times. It should have been inevitable. Then, for five years, it seemed inconceivable. When sat there tortured, beaten and waiting in Grini and then Stutthof, Reidar Kvammen was not just a football man.

|

| Reidar Kvammen |

The Whisperer

It was Asbjørn Halvorsen’s turn to be thrown into Grini Concentration Camp in 1942. By day, he had become the head of personnel at pharmaceutical company Nycomed during the sports strike. By night, he was helping the resistance be heard.

It was Asbjørn Halvorsen’s turn to be thrown into Grini Concentration Camp in 1942. By day, he had become the head of personnel at pharmaceutical company Nycomed during the sports strike. By night, he was helping the resistance be heard.

Whispering Times was a two-page typewritten newspaper that began after radios were confiscated in late 1941. Alongside his six co-conspirators, Assi helped circulate foreign affairs news from a basement flat barely 150 metres behind the Royal Palace. By then it was called the Oslo Palace by nominal ‘president’ and resident Vidkun Quisling.

On 7th August 1942, exactly six years to the day since Halvorsen led his nation to victory in front of a dismayed Adolf Hitler, Assi was arrested. Whilst Kvammen wound up east in Stutthof, Halvorsen was sent to Natzweiler-Struthof, a Nacht und Nebel (‘Night and Fog’) camp near Strasbourg, where political activists would be sent to ‘disappear’.

The Natzweiler prison guards were football men. They knew the great HSV team of the ’20s. They knew the Norway team who won bronze in Berlin in ’36. They couldn’t believe that the great Asbjørn Halvorsen was a political prisoner in a camp where Norwegians came to die. Assi exploited the football men, working translation jobs and administrative tasks, all with the aim of gaining preferential treatment for the Norwegian prisoners.

Trygve Bratteli, who would later become Norwegian prime minister, should have died at Natzweiler. He’d befriended Halvorsen, though, whose earnt favours won Bratteli the medical attention that saved his life. Halvorsen was the camp’s optimist, whispering along outside information and keeping up morale, helping compatriots die with honour or live on with vigour.

By 1945, most Norwegians had been sent to a Natzweiler annex in Vaihingen an der Enz, near Stuttgart, a repurposed camp meant for deserting the sick and dying. Ever the optimist, Halvorsen asked Bratteli to run lectures for the prisoners in Vaihingen, to discuss the reconstruction of Norway and the European continent after they’d won liberation. An epidemic of typhus left it a death trap, but they fought on. Halvorsen contracted the typhus, but he made it through.

The Spirit

Asbjørn ‘Assi’ Halvorsen was not a relatable man because we make him not relatable. We say so, because it’s easier to abide by an adage like ‘stick to football’ than to relate to a man like Halvorsen. Assi was not just a football man. He was a captain, a coach, a leader, a survivor, a whisperer. The resistance. When he went into that meeting with Josef Terboven, he had a choice: be relatable to those eighty years from now and forgive the efforts of sportswashing, or tell Terboven that no man, woman or child would stand for what was being proposed.

Asbjørn ‘Assi’ Halvorsen was not a relatable man because we make him not relatable. We say so, because it’s easier to abide by an adage like ‘stick to football’ than to relate to a man like Halvorsen. Assi was not just a football man. He was a captain, a coach, a leader, a survivor, a whisperer. The resistance. When he went into that meeting with Josef Terboven, he had a choice: be relatable to those eighty years from now and forgive the efforts of sportswashing, or tell Terboven that no man, woman or child would stand for what was being proposed.

Assi chose to remember that his sport, our sport, the great sport of football could prove the basis of free civilisation.

There are rules in football, and within those confines is a contest for honour. As a coach, Halvorsen would send out eleven men to risk harm to themselves knowing full well that even his team of nobodies could beat the evermore prepared and drilled and favoured Germany. There is exactly this honour in football where there was none in what the sportswashers wished to accomplish.

After the war, Assi rebuilt the entire football association. He rebuilt the entire district-based league system to give the country its national league. “Matches between teams at the bottom of a league are just as interesting as the matches at the top,” he justified. He was truly a man who understood the honour and spirit of football.

|

| A younger Asbjørn ‘Assi’ Halvorsen in the 1920s |

Halvorsen died in the winter of 1955 at 56-years old. One too many cold trips to Northern Norway for a man who’d barely survived the very worst. His name was forgotten for years. He’d made his name as a player abroad, the coaching role wasn’t respected till after he’d created it, and the club he played for folded. But what he left his country was a guiding spirit. A spirit in a shade of bronze that would mean more than any gold ever could.

Harald Evensen, vice president of the Norwegian Football Association, wrote the following in a book written for the ten-year anniversary of the Bronze Team, a year after liberation:

If sport is to have meaning, it must be to inspire. It must not be an end in and of itself, but a means to an end; not a means of achieving a tenth of a second better or a few centimetres more or less, but a means of creating a healthy and strong next generation - both spiritually and physically.We’ve watched the youth rise up so many times before, when it was the honour and glory of the country that mattered most. We saw that most clearly throughout the War, our hardest years of need. Against these benchmarks, no records no sporting fame nor a national championship won or lost matter at all.But such a goal cannot be achieved without hard work.The generations who take over the legacy of the ‘Bronze Team’must be willing to work hard. A legacy is not demanded, butbestowed.

In 1940, the Bronze Team had to ask themselves: were they just football men? They answered unequivocally. They denied sportswashing. They stopped playing football because they loved football. They led a resistance. The Bronze Team isn’t Norway’s true golden generation because of what they did on the pitch 1936 in, but because of what they did off the pitch in 1940.

Halvorsen’s team were not just football men.

|

| The bust in memory of Asbjørn ‘Assi’ Halvorsen |

References

Alexandersen, Arne; Gravdahl, Gulbrandsen, Erling; Halvorsen, Asbjørn; Erik; Haabeth, Ingeborg; Martol, Christian; Martol, Sidsel (ed.) (1940-1941) Whispering times.

Bratteli, Trygve (1980) Fange i natt og tåke. Tiden.

Eriksen, Torbjørn Giæver; Fjørtoft, Jan Åge; Lindseth, Ketil; Larsen, Jan-Erik; Wetland, Morten (2016) Helt glemt. Available: www.josimar.no (accessed: 26 September 2023).

Henriksen, Kristian; Horn, Fredrik (ed.) (1946) Bronselaget: en gullalder i norsk fotball. Electronic reproduction, Nasjonalbiblioteket Digital.

Krüger, A.; Murray, W.J. (2003), The Nazi Olympics.

Lapidus, Leif (1946) Våre Egebergvinnere.

Ottosen, Kristian (2004) Nordmenn i fangenskap 1940–1945.

Smith, Nils Henrik (2016) Ringenes herrer. Available: www.josimar.no (accessed: 26 September 2023).

Tiden Tegn (1937) ‘Reidar Kvammen til Arsenal?’. 21 May.

The Spirit of the Vikings (1939-1945) [Radio Programme] WNYC, Royal Norwegian Information Services.

Written by Brendan Husebø (@BrendanHusebo) and kindly given to The Football History Boys (Follow us on Twitter/X: @TFHBs)

Comments