1949: A Year in Football History - 'Will Ye No’ Come Back Again'

It's 1949 and football, as well as the UK, is recovering from the Second World War. For Scott Dixon this year is an important one personally, the year his Grandad transferred from Hearts to Northampton. He has written the story for The Football History Boys...

|

| Arthur Dixon - Northampton Mercury |

My Grandad, Arthur Dixon, played professional football in the 1940s and early 1950s. As a young child, I struggled to grasp that this ageing man with a crumbling hip, slowly deteriorating short term memory and a long-departed perfect sense of hearing, could ever have been in the required physical shape to play at all, let alone to an elite level.

Of course, time catches up with us all and it transpired he had a successful career - particular in Scotland where he played wartime football as an inside-forward for Queens Park from the age of 18 while also serving in the Home Guard. His performances at Hampden gained him international recognition with a Scotland call up to face England in early 1942 only for that ambition to be cruelly snatched away on account of his Englishness by ‘accident of birth’.

Averaging over 20 goals per season, expectation rose in the Scottish press that he would move to Rangers and join his father Arthur Sr, who had played at Ibrox between 1917 and 1926, and was operating as a trainer, physiotherapist, and general assistant to legendary manager Bill Struth. However, Rangers never became a viable option. They had been Scotland’s dominant team before and during the war, meaning the required standard and expectation to succeed would have been extraordinary. Most significantly, there were concerns regarding any potential accusations of nepotism if form or ability failed to merit the opportunity presented in Govan. Therefore, when Arthur left the amateurs of Queens Park behind in 1945, it was for Clyde, then based in the southeast of Glasgow, before eventually transferring to Heart of Midlothian in 1947.

After just over two seasons in Edinburgh he moved onto Northampton Town and would eventually finish his career in and around the Midlands. I have known these basic facts for many years, but I have never understood the supporting information that favours the mere statistics. Why did Arthur decide to move to Northampton in 1949? How did that impact him and his family? What kind of English footballing universe was he entering? How was the game changing around him?

|

| Northampton Town's County Ground |

Stewart was approximately 10 years younger than my Grandad but made the transition to England much earlier in his career, arriving at Bury in 1952, so does provide an idea of the experience of a Scottish player heading south. Imlach went onto have his most notable club success with Nottingham Forest, winning the FA Cup in 1959 and was part of Scotland squad at the 1958 World Cup in Sweden. In telling Stuart’s tales, Gary Imlach provides invaluable information about the financial income and security of a footballer in the late 1940s and early 1950s, of which much was limited by the draconian maximum wage and the employment restricting ‘retain and transfer’ policy that left the clubs with all the power and players as no more than pawns.

In 1949, the maximum wage for British footballers was £12 per week, reduced to £10 in the close season. Comparatively this was around double that of the average manual worker so should not be dismissed as insignificant, even if it cannot come close to modern earnings. However, Imlach reveals that in his father’s time, approximately only 20% of players were actually paid the maximum wage. Arthur may have been a regular for Hearts during his first season, but 1948-49 and even more so the start of 1949-50 had seen him fall out of favour. Additionally, Northampton Town had finished the 1948-49 season as amongst the lowest ranked league teams in the country, so to assume Arthur would be paid the maximum wage at either club would be fanciful. Yet any financial improvement, or at very least potential financial improvement, would be welcomed.

Britain was still recovering from the aftereffects of the Second World War. Rationing didn’t end completely in the UK until 1954 although by 1949, some restrictions had been lifted. Therefore, it would not be unreasonable for anyone to consider financial circumstances before committing to such a career choice. On the other hand, contemporary newspaper reports support the theory that Arthur’s move to Northampton was for genuine footballing, rather than financial, reasons.

Firstly, Hearts were unable to fulfil Arthur’s desire to play games. His first season at Tynecastle saw him become an established part of the squad but year on year, his game time reduced and by September 1949 he had submitted a formal transfer request to manager Dave McLean. Clearly concern had been growing for some time and the request may not have been the first such expression of discontent. The request stated that in the year since a previous conversation “I could count on the fingers of one hand how often you have called on my services”. Substitutes were not introduced into Scottish football until 1966 and Arthur was regularly finding himself first reserve but with little prospect of game time. There was a sense of resignation that his Hearts career was over stating “it is quite apparent that I am not up to the Hearts standard, in your opinion”.

On the back of fears that his time in the game was being seriously compromised if he remained in Edinburgh, Arthur argued he “still had a number of years football ability that might be appreciated elsewhere”. While the letter was courteous, it left no doubt as to how discouraged he was, concluding with a desperate “I want to PLAY”. The Sunday Mail, the Sunday equivalent of Glasgow’s red top Daily Record, sympathised with Arthur’s position arguing it was strange that “an inside-forward of Dixon’s calibre can’t get a game when nearly every other team in Scotland would open the gates to let him in”. Even more perplexing was the response from the Hearts board of directors.

|

| Aberdeen Press & Journal - 20/10/1949 |

On the 25 September 1949, the Sunday Mail reported that the Hearts board were unlikely to approve the transfer request as Arthur was “a prime favourite with some of the Hearts people, as he is with the fans”. It must have been incredibly frustrating for a player whose talents were well regarded and was popular with the support and important figures within the club, that he was not getting the opportunity he felt he deserved. A move to Patrick Thistle, where his father had become part of the management team having followed former captain Dave Meiklejohn from Rangers, was mooted, and a bid was reported from Aberdeen, but a move to England had always appealed.

As early as 1945 when Arthur was considering his professional options when leaving Queen’s Park, he told the Sunday Post he “would like to go south”. During the war he had played as a guest for Middlesbrough against Newcastle and was enthralled with the prospect of regularly playing in England. On 16 May 1945, the Daily Record claimed there was “no doubt” that Arthur wanted a transfer to England. With war in the Pacific continuing, the Record expressed concern that the ongoing situation may limit Arthur’s English options at that time. Arthur was training as an engineer and would have required permission from the Ministry of Labour to switch jobs. Furthermore, he intended, as he ultimately did, to qualify as a physiotherapist (the same role his father performed for Rangers) and attended Glasgow’s Anderson College after work to continue his studying – moving south in 1945 may have limited his educational ambitions. None the less, the desire to test himself in the English League had been long standing.

In early November he got his move, joining Northampton Town for a reported £6000 (approximately £174,000 in today’s money). Northampton officials had visited Tynecastle for a reserves match in which Arthur was to be specifically played in order best represent himself to his potential purchasers - the Hearts management had relented with their objections - but it was rendered unnecessary as the Cobbler’s sealed the transfer before the game amid fear of being usurped from interest elsewhere.

|

| Daily News - 14/11/1949 |

The Northampton based Mercury and Herald seemed enthused by the signing, claiming Arthur was “far too good to be wasting his talent in the second team” (at Hearts) protesting he had only been kept out of the Hearts line up by “the brilliance of both Alfy (sic) Conn and Jimmy Wardhaugh”. Alfie Conn, whose son, Alfie Jr, is one of the few players to play for both Rangers and Celtic in modern times, became a lifelong friend of my Grandad’s while Conn and Wardhaugh are regarded as royalty in the history of Heart of Midlothian: joining Willie Bauld in forming their ‘terrible trio’ during the 1950s. Perhaps Arthur’s inability to break into such a talented Hearts frontline should offer historical comfort.

A move south may not have been the frenzied excitement of opportunity for all involved. Britain in 1949 lacked the transport infrastructure of the later part of the century, certainly there was no motorway network, and a 350-mile journey between Northampton and Glasgow, which stands at approximately five and a half hours by road today, would have felt immeasurably distant. My Grandma told tales of leaving behind friends and family with minimal guarantees of when or even if they would be re-united, while Scotland itself developed almost mythical status in her mind. She often recalled performing her own emotionally charged rendition of the haunting and melancholy Scottish lament ‘Will Ye No’ Come Back Again’ on her journey away from childhood familiarity.

Arthur and family landed in an English footballing landscape where Portsmouth were Football League Champions. The Observer reported their triumph on the 24 April, declaring they can “very properly claim to be the best of the season” following a decisive victory away to Bolton Wanderers. The article praised Pompey stating they played the “most consistent and effective football and are worthy champions in every sense”. Portsmouth were the highest goal scorers in the league and only behind Birmingham City with their defensive resilience. Three days later, the local newspaper Evening News joyously looked forward to their celebratory trophy presentation and parade, comparing the excitement with “memories of April 29, 1939 when Jimmy Guthrie and his lads brought the FA Cup to Portsmouth for the first time”.

|

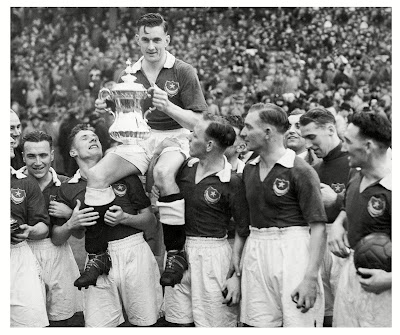

| Portsmouth, 1939 FA Cup Winners |

The league trophy would be presented almost exactly a decade later and the Evening News suggested “celebration of the League Championship victory will dwarf everything in the past”. While the article no doubt meant this comparably to the cup win, given the global events of the previous decade, a rare outpouring of joy would offer a sprinkling of colour to a black and white world. In addition, the newspaper confirmed the attendance at the trophy presentation of Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, the iconic Second World War Military Commander, who was President of Portsmouth Football Club between 1944 and 1961, providing a further reminder that football, like the rest of the world, was somewhere between a bright future and an anxious past.

From Portsmouth at the summit of their English footballing Everest, it is possible to follow the path down past Manchester United, past Everton, around the Second Division duo of Tottenham Hotspur and Bradford Park Avenue, before sinking further beyond Bournemouth and Boscombe Athletic, Gateshead and New Brighton. At sea level, only just keeping their heads above the water was Northampton Town. The Cobblers had finished third from bottom of the Third Division South at the end of the 1948-49 season, narrowly avoiding the threat of applying for re-election on goal average. The jeopardy of automatic relegation from the bottom tier was decades away so perhaps the Cobbler’s felt comfortable, even in the event they fell into the bottom two, thanks to the ‘I’ll scratch your back’ mentality of club owners at the wrong end of the table. Northampton’s fixture list for the 1949-50 season also demonstrates a lost past where paying supporters, and presumably the income they brought, were treated as a priority.

From Portsmouth at the summit of their English footballing Everest, it is possible to follow the path down past Manchester United, past Everton, around the Second Division duo of Tottenham Hotspur and Bradford Park Avenue, before sinking further beyond Bournemouth and Boscombe Athletic, Gateshead and New Brighton. At sea level, only just keeping their heads above the water was Northampton Town. The Cobblers had finished third from bottom of the Third Division South at the end of the 1948-49 season, narrowly avoiding the threat of applying for re-election on goal average. The jeopardy of automatic relegation from the bottom tier was decades away so perhaps the Cobbler’s felt comfortable, even in the event they fell into the bottom two, thanks to the ‘I’ll scratch your back’ mentality of club owners at the wrong end of the table. Northampton’s fixture list for the 1949-50 season also demonstrates a lost past where paying supporters, and presumably the income they brought, were treated as a priority.

Over Christmas 1949 Northampton played back-to-back games with Port Vale, an away trip to visit them in relatively nearby Stoke on Boxing Day with the return fixture one day later - maximising crowds and reducing supporter travel over the festive period. Christmas Day football remained commonplace in England until the midway through the following decade, carrying on in some regard until 1965, and the only reason there was no action on the day itself in 1949 was only because it fell on a Sunday. Christmas fixtures encouraged festivities including the singing of carols, the passing of flasks of liquor around fellow spectators and bizarrely, throwing peel from their stocking oranges at opposition players! From the players point of view, Christmas could be a challenging time with back-to-back games allowing little time with family. My Grandma spoke of Christmases in England in this era where she, eventually with young children, was left for days as her husband slowly travelled the country to play game after game. This must have added to the already existing angst from missing friends and family at home.

Arthur’s debut for Northampton came on the 26 November 1949 at their County Ground (shared with Northamptonshire County Cricket Club) against Walthamstow Avenue in the FA Cup first round. The original Walthamstow Avenue FC, heralding from London E17, were perennial strong performers in the Isthmian League, finishing runners up in 1948-49 having won the title in 1945-46. As a top nonleague team, Walthamstow, and clubs like them would have been as frustrated by the re-election system as much as Northampton were protected by it.

Arthur’s debut for Northampton came on the 26 November 1949 at their County Ground (shared with Northamptonshire County Cricket Club) against Walthamstow Avenue in the FA Cup first round. The original Walthamstow Avenue FC, heralding from London E17, were perennial strong performers in the Isthmian League, finishing runners up in 1948-49 having won the title in 1945-46. As a top nonleague team, Walthamstow, and clubs like them would have been as frustrated by the re-election system as much as Northampton were protected by it.

|

| The iconic County Ground, as it was in the 1970s |

Walthamstow Avenue eventually ceased in their original form in 1988 but through a series of mergers form part of the modern-day Dagenham and Redbridge. In 1936, they showed their credentials when they had defeated Northampton 6-1 in the FA Cup first round but on this occasion, the Cobblers reversed their fortunes with a 4-1 win. Northampton eventually progressed through the cup, exceeding expectations to reach the fifth round only to lose 4-2 to Derby County at the Baseball Ground in February 1950 - Arthur scored both Northampton goals that day including one where he was simultaneously knocked out due to a collision with the goalkeeper! These goals emphasised his heading ability, notable for a relatively small man, that earned him the nickname ‘Rubberneck’ from the Northampton support. Overall, his first season in England was a positive one as aside from the Cup run, the Cobblers improved their league position from third bottom to second top, only being denied promotion by league champions Notts County.

Northampton’s run in the 1949-50 FA Cup saw them eliminated at the same fifth round stage as holders Wolverhampton Wanderers. Wolves had claimed the cup in late April 1949 defeating Leicester City. Wolves were overwhelming favourites against Second Division Leicester and the Observer reporter felt underwhelmed by the simplicity of their win. They declared the result was “according to expectations” and “only at the beginning of the second half, when Leicester had scored one against Wolverhampton’s two goals and seemed on the verge of drawing level, did the excitement become tense”. The match finished 3-1 as Wolves secured their first FA Cup since 1908, having lost finals in 1921 and 1938, and this victory marked the start of an old gold era for the club.

Northampton’s run in the 1949-50 FA Cup saw them eliminated at the same fifth round stage as holders Wolverhampton Wanderers. Wolves had claimed the cup in late April 1949 defeating Leicester City. Wolves were overwhelming favourites against Second Division Leicester and the Observer reporter felt underwhelmed by the simplicity of their win. They declared the result was “according to expectations” and “only at the beginning of the second half, when Leicester had scored one against Wolverhampton’s two goals and seemed on the verge of drawing level, did the excitement become tense”. The match finished 3-1 as Wolves secured their first FA Cup since 1908, having lost finals in 1921 and 1938, and this victory marked the start of an old gold era for the club.

Stan Cullis had become manager in 1948 and alongside England captain Billy Wright, he presided over a period of prevalence that culminated in them becoming Champions of England for the first time in 1954. This would eventually lead to the Molineux floodlights, Honved, Gabriel Hanot and the accepted origin story for the Coupe des Clubs Champions Europeens. In addition, the first World Cup for twelve years was just around the corner and, having rejoined FIFA in 1946, the Home Nations were eligible to qualify for the first time with the Home International Championship of 1949-50 acting as a de-facto qualifying group.

Both England and Scotland would quality but the faux grandiose of the Scottish Football Association declined their invite based on not being British Champions. The seeds of emergence of the European Cup and the growth in relevance of the World Cup showed that, even with the Scottish reluctance to engage, the game was becoming global!

Overall, the significance of football in 1949 highlights both continuity and change in a post war world. Football remained a distinctly working-class profession with the restrictions on trade and salary threatening to be unreasonable. Some clubs plodded along at the lower echelons of the leagues with, thanks to the benefit of the re-election system, minimal consequence for sporting failure.

|

| The British Home Championship trophy |

Furthermore, the importance of the English or British game exceeded, for many on these islands, anything on a continental or global scale, such as Scotland prioritising the Home International Championship over the World Cup. Partly thanks to the re-establishment of the World Cup, a new dawn was appearing on the horizon where serious international competition for the Home Nations would soon become a reality. Furthermore, could Wolves captain Billy Wight possibly have comprehended, as he lifted the FA Cup, that his team would help take the game on a pan-European odyssey – the eventual consequences of which being celebrity and riches for players that would be unimaginable at the time. Football was changing, but it’s hard to accept that anyone really realised.

Written by Scott Dixon and kindly given to The Football History Boys (Follow us on Twitter/X: @TFHBs)

©The Football History Boys, 2023

(All images borrowed and do not belong to The Football History Boys)

(All images borrowed and do not belong to The Football History Boys)

Comments