The Crest Dissected: Stoke City

The last two decades have seen an increasing number of professional football clubs across Britain review, revamp and redesign their official crest or badge as part of a continuing drive to modernise and commercialise the game. The latest generation of crests are rarely designed to demonstrate and commemorate the history and heritage of the club in question with the primary concern now being to create something that is simple, sleek and aesthetically appealing. Whether you agree with this process of evolution and modernisation is a different debate for a different time, but it is clear that the vast majority of clubs have bought into this new trend, often with a mixed response from supporters.

The last two decades have seen an increasing number of professional football clubs across Britain review, revamp and redesign their official crest or badge as part of a continuing drive to modernise and commercialise the game. The latest generation of crests are rarely designed to demonstrate and commemorate the history and heritage of the club in question with the primary concern now being to create something that is simple, sleek and aesthetically appealing. Whether you agree with this process of evolution and modernisation is a different debate for a different time, but it is clear that the vast majority of clubs have bought into this new trend, often with a mixed response from supporters.Stoke City implemented their current crest in 2001 as part of a broader range of initiatives that were a direct attempt to modernise the club following the opening of the Bet365 Stadium (then known as the Britannia Stadium) four years earlier. The club had previously used various manifestations of the city of Stoke-on-Trent coat of arms as their official crest, which they had first adopted in 1912, yet the new design saw the badge completely restructured. It is a perfect example of the new modern style that is being assumed by clubs across the country - it is simple, sleek and looks great on a mug in the club shop. However, it provides little insight into over 150 years of the club’s history in which it has been a central feature of the region’s sporting identity.

Formation Date

The most pronounced characteristic of the modern crest is the club’s claimed date of formation, 1863, which is proudly emblazoned at the centre of the badge. In theory, this makes Stoke City the second oldest surviving professional football club in England and the oldest in the Football League following the relegation of Notts County in 2019. However, the club’s formation has been the source of much debate, discussion and uncertainty with recent research indicating that it is improbable that a formal football club existed in North Staffordshire until 1868.

The traditional narrative claims that the club were formed under the title of Stoke Ramblers in 1863 by four former public-school boys who had attended Charterhouse School, where a dribbling form of the game was widely played. These four Old Carthusian’s supposedly arrived in the region to become apprentices with the North Staffordshire Railway and are commonly named as Armond, Bell, Phillpott and Matthews. Having participated in football whilst at Charterhouse they wished to continue playing the game and decided to establish a football club in Stoke, thus introducing the game to the region.

|

| Charterhouse |

However, this narrative is undermined by inaccuracies and a complete lack of evidence. The Charterhouse School records do not refer to a Bell or Phillpott attending the institution and although there were pupils under the name of Almond (an amendment of Armond) and Matthews they would have been aged 12 and 13 respectively in 1863 and had yet to finish their studies. Furthermore, club historians admit that the first game that Stoke Ramblers contested was in 1868 and that many details ‘remain sketchy’ – hardly a ringing endorsement!

Recent research has demonstrated that the claimed formation date of 1863 is little more than a myth and that Stoke City were actually formed five years later. In 1868 an article published in The Field magazine stated that ‘a new club has been formed in Stoke-upon-Trent for the practice of association football under the charge of H. J. Almond’ whilst that same year the Staffordshire Sentinel reported that it was ‘a new club, having only started this year’. The club’s founder, Harry John Almond, had been a prominent member of the Charterhouse School football team and is the same figure identified in the traditional narrative (just five years later than claimed) and had arrived in the region to work as a civil engineer. It is important to remember that not all myths are entirely false, but rather than certain details become embellished or misconstrued over time.

In 1870 local publications were correctly stating that Stoke Ramblers had been formed in 1868, yet by the mid-1870s this narrative had already started to alter with the Athletic News commenting that ‘some uncertainty prevailing as to whether it was first instituted in 1866 or 67’. By the 1880s regional and national newspapers were reporting that the club had been established in 1865 and this imprecision continued until the turn of the century. In 1905 The Book of Football, then perceived to be a prominent text on the history of the game (although later found to have included several errors), stated that the club had been formed in 1863 ‘by some Old Carthusians’. This story and date have since been repeated with little critique over the following century.

So how did the 1863 myth emerge and become entrenched? Harry John Almond, departed the region after the club had participated in its first game in October 1868 to continue a career in civil engineering that would see him travel to Europe and South America. The lack of substantive long-term engagement from the club’s founder would have accelerated the uncertainty surrounding the story of the team’s origins. Who would have been able to provide a more accurate account of how Stoke Ramblers had first been instituted than the man who had formed the club? This would have been further compounded by the extensive changes in membership that the club experienced during the first half-decade of its existence. By the early 1870s only two of the original players who participated in the inaugural season were still active members of the club. With no records of Stoke Ramblers’ early history being preserved it would have been through word of mouth that successive generations passed on knowledge of the club’s beginnings thus, much like a game of Chinese whispers, the story gradually became distorted over time.

The club initially adopted the title of Stoke Ramblers, which signified that they did not initially have a permanent ‘home’ ground to play on, but in 1870 dropped the moniker and became simply known as Stoke or Stoke-on-Trent Football Club. It would not be until 1925 when Stoke-on-Trent was granted city status by King George V, in recognition of the pottery and ceramic industry for which the region was renowned, that the club was retitled Stoke City.

Red and White Stripes

The most striking feature of the modern Stoke City crest are the red and white stripes that act as the backdrop for much of the badge. This is a direct reference to the traditional red and white vertical striped jerseys that the club has used in various forms for over 100 consecutive seasons – something that is perceived by supporters to be central to the club’s identity.

However, red and white has not always been the adopted colour of Stoke. During its formative years the club initially played in blue and black horizontal hoops (sometimes referred to as navy and cardinal) or on occasions simply used plain white jerseys. It was not until 1883 that there was a definitive switch to red and white stripes, yet even then there would be a need to adopt alternative colours before the turn of the century.

|

| Red and white stripes are synonymous with Stoke |

In 1891 the Football League introduced a new regulation which determined that each club had to register their official colours, to be used in the design of their kits, and which were recorded in the league handbook. This followed several occasions the previous season where clubs had contested matches in kits that ‘clashed’ resulting in players, officials and spectators having difficulty in determining which team was which. As a result, the Football League insisted that all clubs had

distinctive kits for the forthcoming campaign so that there would be no confusion during the forthcoming campaign.

However, this resulted in several clubs having to adopt unfamiliar colours. This included Stoke who, due to the slow actions of club officials, discovered that Sunderland had registered the use of red and white stripes first. For the following seven years Stoke used a variety of different patterns, including red and blue stripes and black and yellow stripes, but the most common design was a solid maroon jersey. In 1908 the club were demoted from the Football League and registered to compete in the Birmingham and District League, which had no rules determining club colours, enabling Stoke to reclaim their red and white striped jerseys. By the time that Stoke were re-elected to the Football League the competition had abolished any restrictions on the colour of kits, thus allowing the club to continue the use of their red and white stripes.

Key Moments

Many professional football clubs incorporate stars or diamonds into their official crest to mark the number of major honours that have been won. This trend was first popularised by Juventus in 1958 who added a star above their badge to represent their tenth Italian League title, at the time a new national record, and which has subsequently been imitated by several clubs during the following sixty years.

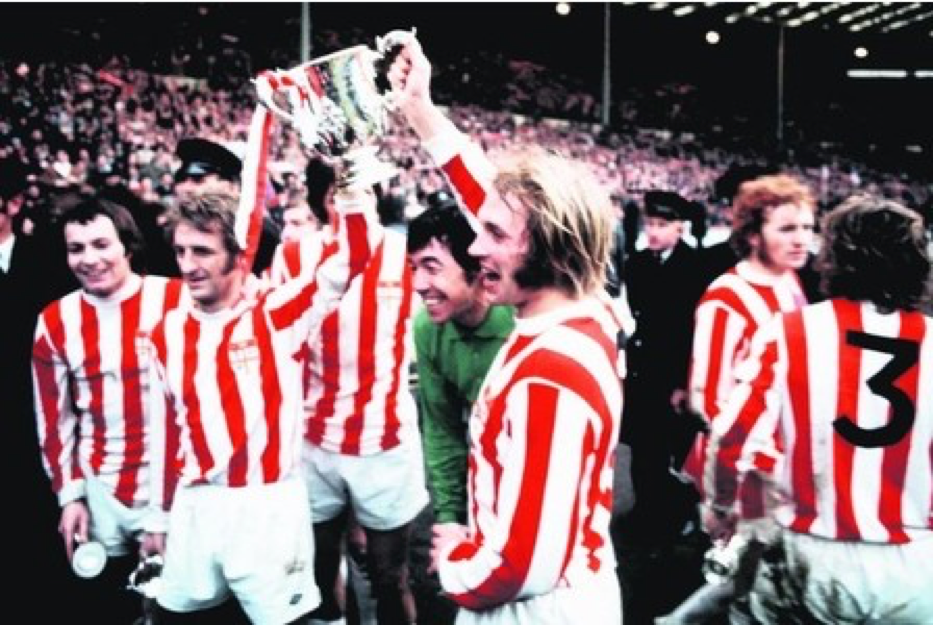

However, there is no star or diamond on the Stoke City crest. In fact, considering the club have been in existence for over 150 years there is a distinct lack of silverware inside the trophy cabinet at the Bet365 Stadium. Stoke have won just one major trophy, the League Cup in 1972, which remains one of, if not the, most iconic moment in the club’s history.

|

| League Cup victory |

Under the guidance of Thomas Charles Slaney, the club emerged as one of the most influential sports clubs in the Midlands and drove the development of the game in North Staffordshire by establishing the Staffordshire Football Association in 1877, one of the earliest county associations in the country. Stoke won the Staffordshire Challenge Cup in both of the competition’s first two years in existence, 1878 and 1879, whilst also emerging as the foremost sporting institution in the region. The success of the club during the mid-nineteenth century enabled it to develop a national reputation which ultimately resulted in Stoke being invited to become a founding member of the Football League in 1888.

However, between 1888 and 1908 Stoke struggled both on and off the pitch. The club finished bottom of the Football League in both of the first two campaigns and in subsequent seasons were often at risk of relegation or were demoted from the competition entirely. This lack of success on the pitch resulted in financial difficulties off it. Stoke had turned professional (officially paying players) in 1885 but quickly discovered that spectators were not willing to pay to watch a losing team - the reoccurring theme was that the gate receipts rarely covered the running costs of the club. In 1908 Stoke went bankrupt but were saved by a consortium of local businessmen, although the team had to drop into the Birmingham and District League.

The 1930s and 1940s were the next successful period in the club’s history. Stoke were promoted to the First Division in 1933 and Bob McGrory, who had made over 500 appearances for the club as a

player, gradually built a team that consisted primarily of young, talented local players. Stanley Matthews, who became one of the most renowned players of his generation, was a central feature of the Stoke side during the period and characterised the growing prominence of the club. Such was the promise of the team that in April 1937 over 51,373 spectators watched the side play Arsenal at the Victoria Ground, a club record attendance, which demonstrated the popularity of the side.

|

| A young Stan Matthews with Bob McGrory |

The Second World War, which resulted in the suspension of the Football League, robbed many of the club’s star players of the prime years of their careers with many scattered across the country as they joined the armed forces. When hostilities had ceased Stoke came within one game of winning the First Division title during the 1946/47 season, with any hopes of silverware ended on the final day of the campaign following a defeat to Sheffield United, although the eventual 4th place finish remains the club’s highest ever league position. However, the campaign also signalled the end of Matthews’ first spell at the Victoria Ground after the star winger was controversially sold to Blackpool following a bust-up with McGrory – within four years the club were back in the Second Division.

The appointment of Tony Waddington as manager in June 1960 marked the start of Stoke’s golden era. He initially adopted a pragmatic style of play in which he implemented the ‘Waddington Wall’, a tactical innovation in which two defensive midfielders were deployed in front of the back four, which enabled team to win the Second Division title in 1963 and finish runners-up in the League Cup in 1964, losing the final to Leicester City. The club were also boosted by the return of Stanley Matthews in 1961, who saw out the twilight of his career at the Victorian Ground until he retired at the age of fifty.

However, the early 1970s saw Stoke emerge as one of the most entertaining sides in the country with Waddington encouraging a new swashbuckling, exciting brand of football. The team assembled was brimming with star quality, talent and experience with the attacking innovation of Alan Hudson, Jimmy Greenhoff and John Ritchie combined with the defensive resilience of Gordon Banks, Dennis Smith and Mike Pejic. Stoke reached two FA Cup semi-finals in consecutive seasons in 1970/71 and 1971/72, losing on both occasions to Arsenal, before winning the League Cup in 1972.

However, in January 1976 disaster struck when the roof of the Butler Street stand was blown off during a storm, with the resulting £250,000 repair bill throwing the club into financial turmoil. Stoke had to sell their star players to balance the books and the team was slowly disbanded, with Waddington resigning in March 1977.

By the end of the 1984/85 season Stoke had been relegated to the Second Division, after securing just 17 points and winning only three games, and by 1990 had dropped into the third tier of English football. There was some brief respite for supporters during the early 1990s following the arrival of Lou Macari as manager in May 1991. The charismatic Scotsman guided the club to promotion in 1993, a year after winning the Football League trophy at Wembley, yet any hope of a new golden era at the Victoria Ground was swiftly ended when he departed in the summer of 1993 to join boyhood club Glasgow Celtic.

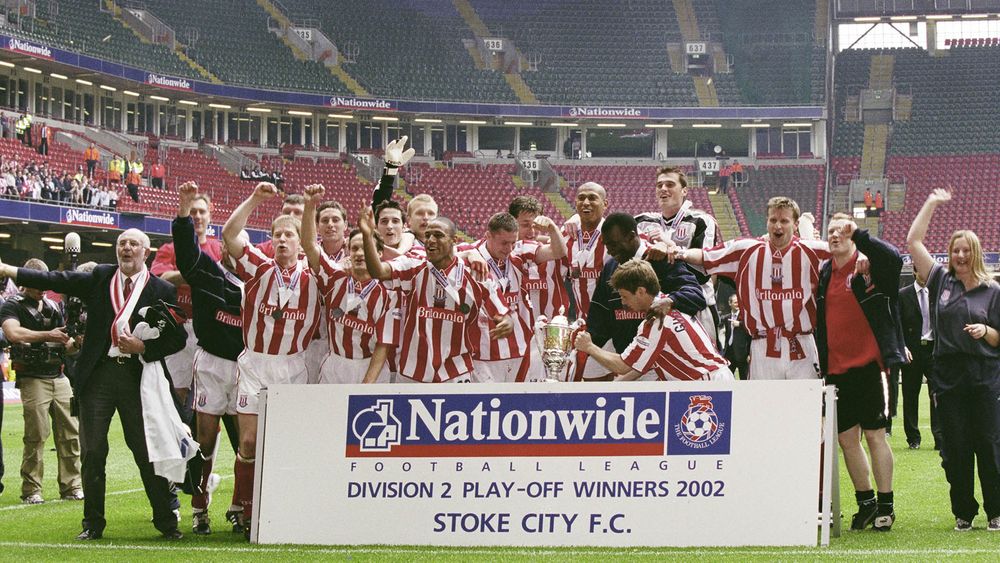

In 1997 Stoke relocated to the Britannia Stadium (now renamed the Bet365 Stadium) but, in typical Stoke fashion, suffered relegation in the first season at their new home. Two years later the club were purchased by an Icelandic consortium led by Gunnar Gilslason who immediately instilled his fellow countryman Gudjon Thordarson as manager. Under the new regime Stoke won the Football League trophy in 2000, in front of over 85,000 supporters at Wembley, before winning the 2001/02 play-off final at the Millennium Stadium, beating the so-called ‘South Stand Jinx’, to secure a return to the second tier of English football.

|

| Play Off Victory in 2002 |

The most recent period of success was stimulated in May 2006 when former chairman Peter Coates bought the club from the Icelandic consortium for over £6 million. He appointed Tony Pulis as manager one month later and within two years Stoke, courtesy of a goalless draw on the final day of the 2007/08 season, secured promotion to the Premier League. The club spent ten consecutive seasons in the top flight, with the highlight being an FA Cup Final appearance in 2008, before being relegated to The Championship in 2018

This piece was kindly written for @TFHBs by Martyn Cooke - Follow him on twitter @Cooke_Martyn

The Football History Boys, 2019

Comments