Suffrage and Sport: A Peculiar Relationship

Well then...2016...it's been a funny old year. Perhaps the most controversial moment being Britain's insane idea to leave the European Union. Through social media and numerous television reports, politics has been thrust into the limelight for us all to debate and discuss. But it is not just in the UK, the US political scene has also developed into an increasingly desperate situation with Donald Trump securing the Republican nomination for the presidency. However, despite all the doom and gloom, something has stood strong amongst such uncertainty and been a source of unification - Sport. From Leicester's unlikely title triumph, Wales and Iceland's Euro heroics and Team GB's incredible Olympics in Rio, we have learned that sport can influence the socio-political scene like nothing else.

Well then...2016...it's been a funny old year. Perhaps the most controversial moment being Britain's insane idea to leave the European Union. Through social media and numerous television reports, politics has been thrust into the limelight for us all to debate and discuss. But it is not just in the UK, the US political scene has also developed into an increasingly desperate situation with Donald Trump securing the Republican nomination for the presidency. However, despite all the doom and gloom, something has stood strong amongst such uncertainty and been a source of unification - Sport. From Leicester's unlikely title triumph, Wales and Iceland's Euro heroics and Team GB's incredible Olympics in Rio, we have learned that sport can influence the socio-political scene like nothing else. We wrote a piece last year on the rise of female sport in Victorian/Edwardian Britain and questioned whether increased participation was the vital factor in their later right to vote. This piece is once more going to go back in time to question the influence of sport on both female and male rights at the turn of the century. Football, as we have learned, was the most popular sport c.1900 - with cricket perhaps the only sport with a valid claim to its title. Nevertheless, sport and suffrage encompasses a larger number of games as well as football, each with their own opportunities for social and political fraternization.

So where do we start?...It's a question which we don't really know how to answer so a quick trawl through the newspaper archives shall have to do! In fact a quick observation into the codification of sport and the rise in suffrage from 1860-1930 shows a strong correlation. Indeed, prior to 1860, sports were played under strict class restrictions - street football for example a game for the working class, alongside cock-fighting and boxing. On the other side, pursuits like cricket or croquet were exclusively played by "gentlemen". However, the rise of muscular Christianity in English Public schools during the first half of the 19th century led to a growing interest in physical sports.

Following the anti-climactic 'Great' Reform Act of 1832, the working class of Britain became increasingly disillusioned with the voting franchise. As a result, this would lead to the rise in Chartism and other movements designed to question the government. It should be noted that the rise in suffrage has a direct relationship with the codification of modern-day sports. Indeed the 1867 Reform Act occurring just fours years after the formation of the Football Association - coincidence? Let's find out...

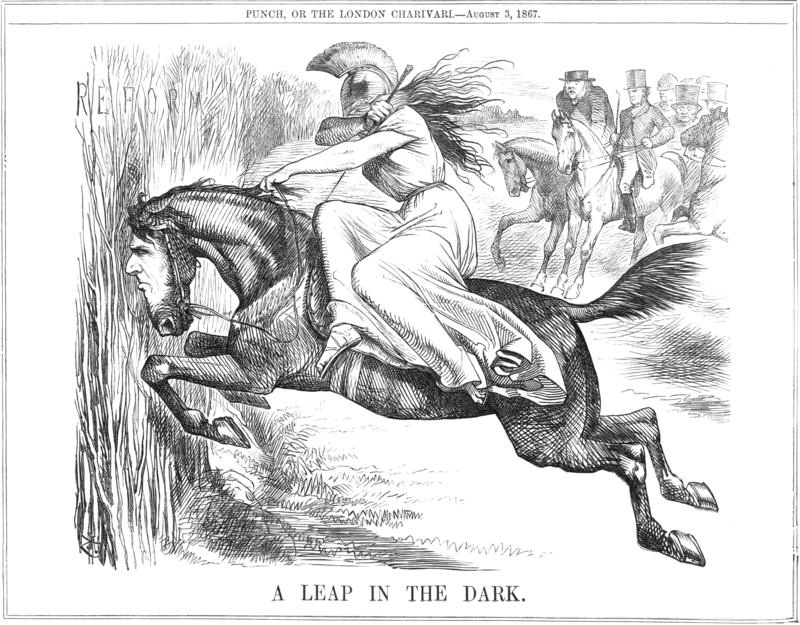

|

| The 1867 Reform Act - Sport (Horse-Riding) used to describe it to the wider public |

Newspapers from the time are amazingly similar with regards to both political and sporting viewpoints. Concerning the 1867 Reform Bill an article found here questions whether or not the enfranchisement of the lower classes is a good idea...

" It may lead to greater prosperity, improved social relations, and a higher state of civilisation. But also it may conduct to revolution and ruin....The present Parliament is emphatically Parliament of the middle classes. They command the representation, and thus control the Government. Any possible Reform Bill must more or less transfer this power from the middle class to the classes below them. It must give this power partially into the hands of the working classes, but it may do so wholly. The middle classes must be greatly weakened; they may be politically extinguished. depends upon data we do not know and cannot discover whether the British, empire shall or shall not be ruled by the trades unions, themselves moved by an irresponsible committee in London or Manchester."Despite the rhetoric and hyperbole of the article - such thoughts were commonplace amongst middle-class political commentators during the late 19th century. Working class emancipation could be found elsewhere in sport - particularly with regards to professionalism,

"It was necessary in fact, first to define a professional foot- ball player and then to decide whether his presence among amateurs should be tolerated. In the result professionals were both defined and condemned to banishment outside the charmed circle within which the amateur resides. With the particular form of the definition there is little or no concern upon: the present occasion. If, however, an independent definition be desired, a professional player of any game, or exponent of any muscular pastime, may be described as a person who is induced to exert himself, not by a sheer and unadulterated love of sport, but also, at least in part, by the prospect of pecuniary reward. As to the admission or exclusion of the professional, the problem is not merely one of a social character; nor, it is believed, does the agitation upon the professional question owe its origin to any pride of class. Gentle- men amateurs have never been too nice in making inquiries concerning the social status of their opponents in any pastime."

What is clear is that the emergence of a genuine working-class was seen as a threat to middle/upper-class dominance in British society. Sport was a platform for those of a lower-income to prove themselves able to compete with their social oppressors. Football was where this was most prominent with the FA Cup a clear example of a 'changing of the guard' throughout the 1870s and 1880s. The 'disease' of professionalism was soon to encapture the game and thrust northern-based players into the limelight as first Blackburn Olympic and later Preston North End wrestled control of the tournament into the hands of the working-class.

|

| Football and Socialism |

Of course, the sporting revolution of the late nineteenth century saw more than just football begin to question social order. Sports which could attract a large amount of spectators encouraged the most fear in the gentry due to such strength in numbers. Rugby League was another bastion of northern solidarity opposed to the union game of the south. As Britain began to shake off its bleak Dickensian image, a fall in food prices and a rise in wages for both skilled and unskilled workers, spectatorism would continue to expand and thrill greater numbers. In Wales however, the union game was surprisingly adopted over league, despite political allegiances more akin to those north of the border. Playing opposite the amateurs of the south gave the Welsh a chance for a new identity moulded on the sport and a chance to showcase themselves like never before.

"Some people say that interest in (Rugby) football is gradually decreasing in the district, and that in another three or four years, perhaps, a couple of thousand people at the outside will go to see our matches. Well, the little affair of Monday night, when the Cardiff contingent of the Welsh team got such a grand reception, does not look like anything of the sort. There must have been quite seven or eight thousand present, and the manner in which they escorted the players up St. Mary-street reminded me of the reception at Limerick, where, as I wired on Friday, there were about 6,000, with breaks, four in-hands, brass bands. &c. Cardiff's reception was, if anything, a trifle more boisterous, but nonetheless sincere. They would not be denied, and shouldered the players in very vigorous fashion."By 1884, another reform act had been passed by parliament. Under William Gladstone the Liberal Party had managed to get one over on their Conservative counterparts and further increase the voting franchise to include all working men in boroughs as well as counties. A year later professionalism in football had been ratified but the Football Association, leaving amateurs licking their wounds and never really recovering. Sport was beginning to become the quintessential aspect of many worker's lifestyle,

"The working man had lost touch with the old self-improving traditions - politics, religion, the fates of empires and governments, the interests of life and death itself must all yield to the fascination and excitement of football."Holt, 1989

Cycling is Britain's most successful sport of the past 20 years, if not of all-time. Towards the end of the century, alongside the increasing numbers participating in football, rugby and cricket, middle-class leisure pursuits were also on the rise. Lawn Tennis, codified in 1874, became 'universally popular' amongst social circles in Britain's more affluent areas - replacing the 'tedious and intolerable' croquet. Cycling was introduced mainly in the 1890s, once more as a middle-class social exercise rather than competitive sport.

|

However, following an increase in leisure time offered to city workers in the decade, the reasonable price of bicycles, led to trips to the countryside and of course, the beach. Sports Historian Richard Holt notes the mass production of the bicycle and the installation of safety precautions as a reason for its rise in popularity. Membership of the Cyclists' Touring Club shot up to nearly 60,000 in 1896, only to drop 15 years later with the development of the motorcar. Despite remaining predominately middle-class, a growing number of workers began to take to two wheels.

There is no shortage in articles relating to both sport and politics around the turn of the century. Some highlight the direct relation of the two and others make note of sport's ability to go beyond political differences. It is evident in a 1908 article, where billiards was played between the Liberal and Conservative parties,

"SPORT KNOWS NO POLITICS.

Liberals and Conservatives in the Listerhills Ward Bradford know how to friends when there political fighting to be done, and the members the Gladstone Liberal Club have paid a visit to the Crowther Street Conservative Club and joined in billiard matches and whist tournament. At the ‘‘smoker” that followed there was some little speech-making. Councillor Dr. Walker offering a welcome to their visitors, and Councillor Redfearn acknowledging the good wishes on behalf the Liberals hoped such interchange of visits would become a permanent feature in their ch#b life."

| Sport breeds national pride like nothing else |

By Ben Jones (TFHB) - follow me on Twitter @Benny_j and @TFHBs

Comments